The first deeper concept that we should dive into is the foundational Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery concept. This is foundational because most of the following practices are built on the continuous integration and continuous delivery as the pipeline to delivery. There are a plethora of tools out there to support this capability, selecting the right tools for your organization is definitely a complex topic in itself, which will vary based on many factors, which I will discuss.

Continuous Integration & Continuous Delivery in Plain Terms

The first and very important thing I am going to start with is these are two related, but different concepts. You can use different tools to separate the duties of Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Delivery (CD), you can also use a single tool, but you should make sure when you build things out that they complement each other. Another way of thinking about the differences, consider CI like a spellchecker as you are writing a document, while CD is like the formatting to ensure that the document is ready to print.

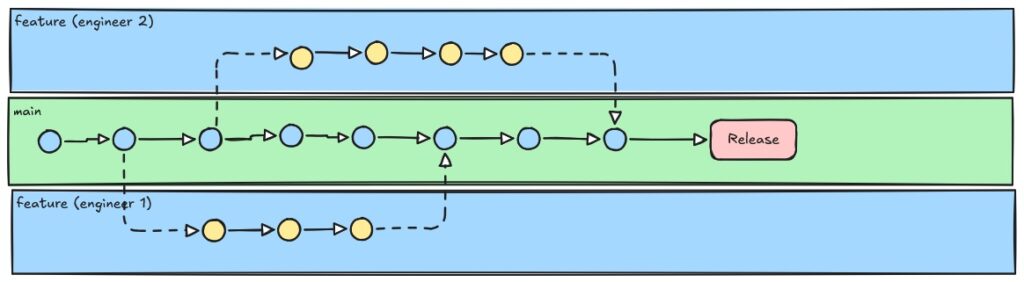

Continuous Integration creates a process in which enables developers to regularly commit code and merge changes into shared branches within source control systems. What this means that it will allow independent developers to work in shared code bases, merging related to unrelated features and fixes to a shared set of components with minimal impact with each other. Continuous Integration should automatically run builds based on changes to those software components and run tests within the code base to validate that nothing has broken with the changes being made, thus catching some of the integration issues earlier in the process.

An important note here, continuous integration won’t magically guarantee bug-free software, it will only catch what you can and do test for. It also cannot replace important processes such as thoughtful code review, which is a critical piece of the software engineering practices that we should be building. The other important thing to understand is that continuous integration isn’t responsible for actual deployment of the code, it is to validate it could be shipped, not the actual shipping of the artifacts.

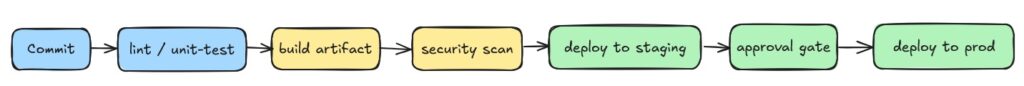

Continuous Delivery will create an automation process that prepares code for release once it completes all checks contained within the continuous integration process. This is purposefully ambiguous because this is the hallmark of the foundational status for this concept. What Continuous Delivery attempts to do is to create a process that will ensure any merged code can be done so in a state in which it is ‘deployable‘. The focus here is to put in checks for whatever that might look like for your technology landscape.

To dig into this a little bit more, continuous delivery is how you build and validate that you can package a software component and then push to an environment in a regular and predictable process. Something that is important to understand is some things continuous delivery will not solve every problem. Due to this, continuous delivery isn’t about “always delivering” or pushing code to production daily, it is about creating the right process and governance to deliver software reliably with the appropriate amount of governance to prevent issues along the way. Something to be aware of and cautious with CD is understanding environmental parity, which is the alignment of the version of applications in DEV, Stage, and Production. Having an established process will help with monitoring the artifacts in the different environments match what was tested and promoted.

An important thing to develop as your team or organization grows in their maturity with DevOps and their CI/CD practices is to automate rolling back of software components in the event of failures at different stages. These capabilities are about creating easy to use practices that will shift the focus from complex and hard to maintain pathways to delivery to focusing on delivering value using a trusted and established process that promotes safety checks along the way.

Why CI/CD Matters for Leaders

Now that we know what CI and CD does, let’s talk about why it is important to invest your team’s time and effort into building a baseline. Building a strong foundational process allows multiple individuals or teams to be working on the same related or unrelated changes in the various components, while preventing conflicts and preventing possible incomplete or simply problematic software before it even hits an environment.

Investing in your CI/CD practices will build the foundation that will drive for focus on delivery of value, eventually reducing manual testing by having a strong foundation to validate, build, test, and deploy code with ease. Here are some business outcomes that I have seen, along with others that we’ve seen gained with DevOps Practices:

- Early detection of issues to avoid outages.

Pipelines will catch bugs, vulnerabilities, and integration problems before they reach production. Since there are now shorter feedback loops teams can find integration issues earlier in the process, which reduces outage risks and lower remediation costs. - Improvement in security & compliance posture.

Using automated “tollgates” to flag vulnerabilities before changes are merged. These objective checks strengthen audit trails and reduce compliance risks. - Better visibility, metrics, and feedback loops.

Data from pipelines shows where teams succeed or struggle. Metrics like deployment frequency and success rates support better decisions. The goal of these metrics is not vanity reporting but actionable insights — leaders should look for patterns that reveal bottlenecks and blind spots. - Business value through increased velocity and dependability.

The use of standard, repeatable workflows shorten release cycles that are reliable. Since teams are spending less time on delivering code to higher environments, this will allow the team to focus more on providing value to the customer and organization. - Industry-specific risk reduction and regulatory compliance.

This reduces compliance risks and avoids the significant financial and reputational costs of audit failures. In industries with SOC1, SOX, or other standards, pipelines provide traceable evidence of change management. Another benefit in making these events traceable is that the cost to prepare evidence for your audits will be reduced.

Something to think through when designing the CI/CD process is understanding the right tool for your organization. There are platforms that will offer the creation of a single storefront for your full system, with others offering full customization with the ‘ownership tax‘ that must be paid with having a strong team to manage the tool fully. When weighing your options, here are some questions or principles to think through and have the team responsible to provide inputs on:

- Do you have the staff capable of maintaining open-source pipelines?

If not, the ‘ownership tax’ can outweigh the flexibility. This means more engineering time on infrastructure versus relying on vendor uptime guarantees. - Is strong built-in compliance reporting required?

Most Platform as a Service (PaaS) providers have strong built-in reporting for your CI/CD process. They’ve built features to meet a large variety of use-cases, which means they likely have it available if you are using their standard process. If you need custom reporting though, you either are dependent on the provider or will need to go with a team-owned open-source solution. - What is your scale you need to build to?

The smaller your organization, the smaller the cost for a platform. Most of the existing platforms are about size and use of the platform, which creates a cost curve. At first a platform might be cheaper, then as you grow and expand, the curve may start to swing back to development of an internal team that will own a custom platform. - Are you able to accept the risk with vendor lock-in?

For faster adoption, using a PaaS solution will speed up setup and integration into your environment. There is a dependency on the provider to setup and provision any agreed setup, which could lead to delays depending on the agreement. If vendor lock-in is a concern, the slower path is to build a custom platform, which requires time to build, test, validate, and roll out to your organization. - Which is more important, speed to see value or control in the long run?

similar to the last point, setup time is shorter typically for a PaaS solution. It will leverage capabilities built and established into their platform. This does have a cost, if your organization has an integration or custom needs, it will depend on support from the platform. If control is more important, then building your own platform is the best solution.

Every architectural decision is a trade-off. Leaders and engineers must align on business needs and risk appetite. The right CI/CD platform isn’t about tools: it’s about delivering shorter cycles, reducing risk, and building trust between technology and the business.

Architecting CI/CD Pipelines

With the business case established, let’s shift to how engineers design pipelines to achieve these outcomes. I want to go over some common terms and models, reviewing their capabilities and their trade-offs. Something to make sure you understand before starting the design step, make sure you understand the needs for the organization both now and in the near future. It is important to think of designing extensibility and flexibility where possible to add in pieces and remove when it makes sense.

In this section I am also going to tackle some concepts that are important to understand when we talk about CI/CD pipelines. This is not an exhaustive list of newer concepts, just some that I wanted to talk through to expose, which I will provide links to additional resources as well.

| Category | Concept | What it is | Trade-offs | Further Reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branching Models | Trunk-based development | Short-lived branches merged daily into main. | Requires strong tests, feature flags, and cultural discipline | Trunk-based Dev |

| GitFlow | Structured branching model with develop and release branches. | Slower feedback and merge overhead | Atlassian GitFlow Guide | |

| Deployment Strategies | Blue-Green | Two production environments; traffic switches between them for zero downtime. | Double infrastructure cost. | Martin Fowler Blue-Green Deployment |

| Canary | Release to a small % of users, then expand if healthy | Needs telemetry & traffic shaping | Octopus Deploy – Canary Deployments | |

| Rolling | Gradual replacement of instances until all are updated. | Some risk of partial downtime if checks are weak. | Kubernetes – Rolling Deployments | |

| Pipeline Infrastructure | Runners/Agents | Execution environments where pipelines run (SaaS-hosted or self-hosted). | SaaS: easy but less control. Self-hosted: more controls, more ops | GitHub-hosted runners |

| Ephemeral Environments | Temporary test envs spun up per PR/branch. Great for collaboration & testing. | Infrastructure cost, cleanup discipline required. | DevOps Ephemeral Environments for Testing | |

| Security & Compliance | SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) | Inventory of all software components, increasingly required in regulated industries. | Overhead to generate/maintain, but essential for supply chain security. | NTIA SBOM Guidelines |

| Policy as Code | Express and enforce rules as code (e.g., OPA). | Steeper learning curve; requires governance culture. | DevOps Policy-as-Code in CD Pipelines | |

| Secrets Management | Securely handling credentials in pipelines (Vault, KMS, OIDC). | Mismanagement leads to breaches. Adds infrastructure dependency. | HashiCorp Vault Intro | |

| Supply Chain Security | Signed commits, SBOMs, artifact provenance, SLSA framework. | Maturity investment required. | SLSA Specification | |

| Delivery Practices | Build Once, Promote | Build an artifact once, promote it across environments (dev → prod). | Needs artifact storage & signing infrastructure | Medium Build once, deploy everywhere |

| Feature Flags | Toggle features at runtime, enabling safe rollouts & trunk development. | Risk of flag debt if not cleaned up. | Martin Fowler – Feature Toggles | |

| Observability | Pipeline Telemetry | Emitting metrics (build time, failures, MTTR), linking commits to deployments & SLOs. | Requires monitoring & cultural buy-in. | DevOps Telemtry Pipelines |

| Performance Enablers | Caching & Build Acceleration | Reuse dependencies/artifacts to shorten builds. | Cache invalidation complexity. | Azure Pipeline Caching |

| Ephemeral Agents | Disposable runners (often containerized) per job for clean, reproducible builds. | Slightly longer spin-up times. | AWS Best Practices for Build Containers |

Trunk-based CI with Rapid Promotion

Designing a system tot utilize trunk-based CI with rapid promotion depends on some level of maturity and willingness from a culture of rich test automation. This workflow focuses on using a single main-line branch, with short lived feature branches that are merged daily to reduce the likelihood that someone will have a merge with a conflict that is harder to untangle and resolve. The benefits for this system is that if your organization has the maturity in testing and speed is important, you can deliver changes more rapidly when using feature flags mixed into the regular deliveries.

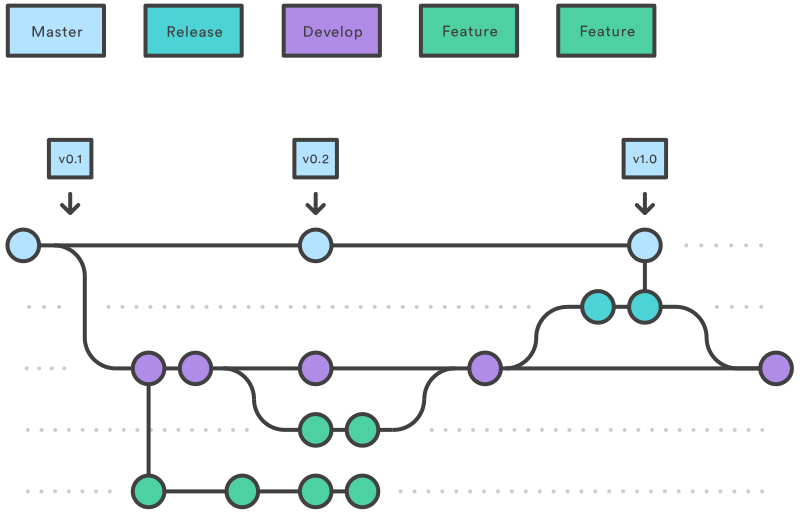

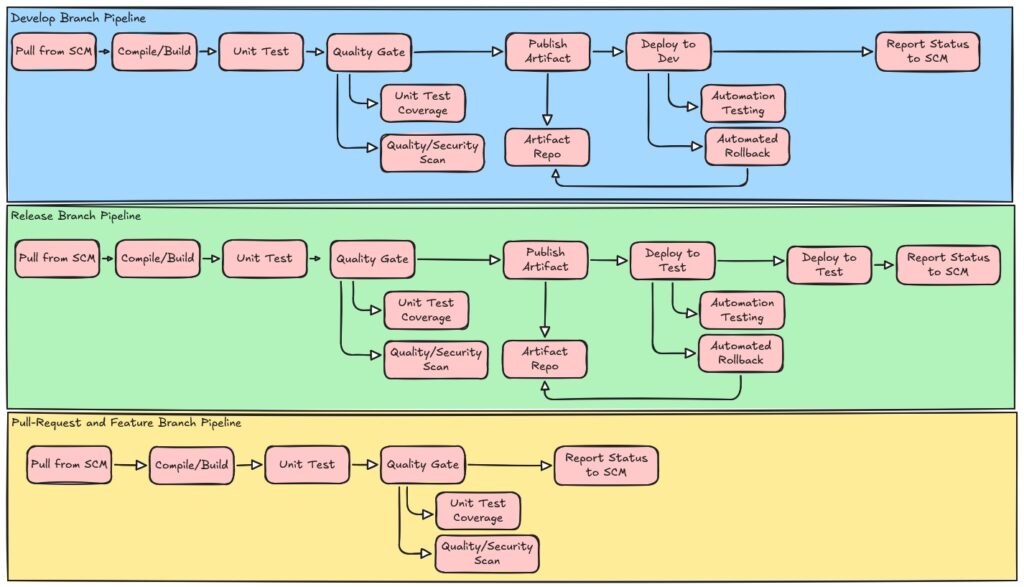

GitFlow with Release Trains

A common branching strategy used at organizations with longer running projects and delivery cycles is GitFlow. The idea with a pipeline based around this flow is that you have a pipeline definition based on the rules of your organization and the branch types or trigger conditions to cause the invocation of the pipeline. GitFlow is a standard and accepted pattern which is also useful for highly regulated organizations and change windows. Something to monitor with this type of architecture is the importance of understanding who else is working in the shared repository and making sure your teams have the discipline to manage branching and proper testing before promoting to high environments.

GitOps for Infrastructure & Apps

GitOps is a modern operational framework for automating infrastructure and application deployment. In a GitOps Flow, Git becomes the source of truth; pipelines reconcile desired vs actual state automatically. This special kind of pipeline that is focused more around infrastructure as code, but can be adapted for application deployments as well. GitOps is a newer pattern, which requires a declarative approach to setup your configurations. This is easier to accomplish in a cloud Infrastructure as Code, because it declares your full environment as code, then when you need to create or modify an environment you have a representation in your code. Continuous Delivery in this type of workflow is about detecting the changes and applying those changes only.

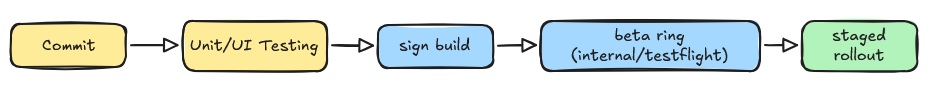

Mobile app Release Train

There are unique constraints when working on a CI/CD pipeline for a mobile application that is published to a marketplace like iOS or Android. Since the marketplace may have requirements such as testing, validations, and specific scan requirements, a modified workflow is required. Most of these changes will involve a merge commit, moving those through unit tests and a UI test on a device farm, which will mimic multiple device types, then proceed with signing a build for actual beta testing. This lifecycle requires diligence on purpose, the goal is to identify stable builds only to go to the general public for both the benefit of the internal organization (your organization) and the marketplace owner’s organization (Google or Apple in the example).

These are just a few examples of pipelines that are fairly standard across organizations, which follow some best practices. Something to also think about, like every other architecture decision, is that there might not be a single “standard flow” that makes sense for your situation. Learning to swap components or pieces from other workflows into your workflow when it makes sense. For example, something that might be useful to insert into an API rich organization is contract-testing, which will register contract producers and any application that consumes that API specification. This is a workflow that may not show up in the standard flow, but it is useful for your situation, then use it.

Another important requirement to always keep in mind is metric collection and requirements around governance of changes. For a startup, I may not be as concerned with a formal process, it’s about rapid delivery of small chunks to see value faster, compared to an organization that has heavy regulations like financial or other regulated industries, which require more rigor in ensuring the correct process has been followed for audit requests for any change. Pick a starting workflow that matches your team’s maturity. As you grow, experiment with hybrid designs, your pipeline should evolve with your business, not remain fixed.

Build a Jenkins Pipeline for CI/CD Workflow

For experimenting with CI/CD pipelines, there are several options to get started. The common free tool that has kept up its popularity overall, is Jenkins. Jenkins is an open-source application that has evolved over years to add third-party plugin providers to enhance capabilities of the base Jenkins capabilities. There are options to run Jenkins locally on your machine directly. For a complete setup guide, you can find a learning path here at Jenkins Guided Tour.

The guide does provide a starter pipeline which will help define a pipeline. This is useful to get started, which I do recommend doing your first pipeline setup before continuing, as it will provide the context as I continue (Jenkins Quick Start). Jenkins has provided a lot of guidance on best practices; here are some concepts to keep in mind in setup:

- Use organization folders. When setting up jobs in Jenkins, use organization folders to map to related multibranch pipelines for access and common scanning methods.

- Use multibranch pipelines. Multibranch pipelines detect branches that contain the expected Jenkinsfile which is the Jenkins specific pipeline control file. Having this setup means that the pipelines will detect new branches and tracks if a new build needs to run systematically instead of manual triggers.

- Monitor your schedules. With auto detection of branches through pipelines, monitor scheduling overload by builds or tasks that aren’t required that will take resources from higher value tasks.

- Avoid resource collisions. When multiple jobs run simultaneously, add controls and monitor collisions that can occur to certain shared services. There are plugins to help monitor the use of lockable resources, understanding your build and pipelines is critical.

Another best practice that I want to highlight before getting started is to leverage central governance for common pipeline logic. Jenkins for example offers both Shared Libraries, which are versioned Groovy libraries kept in a Git repo and loaded into each job. This will expose reusable steps or even an entire pipeline entrypoint. Then in this model, the project repositories will keep a tiny Jenkinsfile that just calls the shared library.

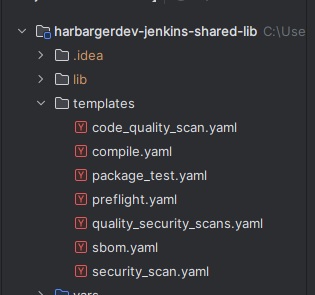

In this pattern, see the below reference for a repo that contains the ‘jenkins-shared-lib’ definitions. I developed a sample project example that has definitions for the steps and an example Jenkinsfile in each repository that can then be added. The folder structure for this project is seen below.

(repo root)

├─ vars/

| └─ harbargerdevPipeline.groovy # exposes a call(Map cfg)

| Jenkinsfile

| .gitignore

| README.mdThe detailed mock pipeline can be found in a Public GitHub repository harbargerdev/harbargerdev-jenkins-shared-lib. This repo gives you a ready-to-fork lab with a working mock pipeline, so you don’t start from scratch. The vars directory contains the logic and requires the caller to pass a Map of input parameters. Then in specific chunks that are for different branches, it will conditionally execute some of the deployment logic, but by default will always execute the core build and test logic.

// Jenkins Shared Library: GitFlow Pipeline

// Supports develop (DEV), release (STAGE), and main (PROD) workflows

def call(Map params = [:]) {

pipeline {

agent any

stages {

stage('Pre-flight check') {

steps {

script {

if (!fileExists('buildArgs.json')) {

error 'Pre-flight check failed: buildArgs.json not found in workspace root.'

} else {

echo 'Pre-flight check passed: buildArgs.json found.'

}

}

}

}

stage('Compile') {

steps {

sh 'mvn compile'

}

}

...

stage('Publish & Deploy to DEV') {

when {

branch 'develop'

}

steps {

script {

echo 'Publishing SNAPSHOT artifact (mock)...'

writeFile file: 'published_artifact.txt', text: 'Artifact published: SNAPSHOT (mock)'

echo 'Deploying to DEV environment (mock)...'

writeFile file: 'dev_deploy.txt', text: 'Deployed to DEV (mock)'

}

}

}

stage('Publish & Deploy to STAGE') {

when {

branch pattern: 'release/.*', comparator: 'REGEXP'

}

steps {

script {

echo 'Publishing STAGE artifact (mock)...'

writeFile file: 'published_stage_artifact.txt', text: 'Artifact published: STAGE (mock)'

echo 'Deploying to STAGE environment (mock)...'

writeFile file: 'stage_deploy.txt', text: 'Deployed to STAGE (mock)'

}

}

}

stage('Ready for Production?') {

when {

branch pattern: 'release/.*', comparator: 'REGEXP'

}

steps {

input {

message 'Ready to publish to production?'

ok 'Continue'

}

}

}

...Once you’ve defined your shared library structure, the next step is wiring it into Jenkins itself. In the Jenkins UI, under Manage Jenkins you can go to System –> Global Pipeline Libraries and then define the name, default version, and the link to the SCM that houses the parent pipeline.

In each application, you can then add the following to the expected Jenkinsfile.

// Jenkinsfile

@Library('harbargerdev-jenkins-shared-lib') _

harbargerdevPipeline()A second approach that is available from Jenkins is the Jenkins Templating Engine, which is a plugin for template-driven, centrally governed pipelines, removing the need for a Jenkinsfile in every app repository. This simplifies the repository setup while also avoiding duplication. In addition, the other benefit of this strategy is that it enforces consistency and reduces risk of pipelines that might drift from the standards.

Here are the setup steps for the Jenkins Templating Engine, with more detailed documentation available at their document hub Jenkins Templating Engine Docs.

- Create a git repository, you can use the same shared-libs repository you setup from the initial shared logic example. All templates go into a directory call ‘templates‘.

- In Jenkins, install the Plugin from the Manage Jenkins section. Once installed, configure the plugin by defining the source for the templates by adding your repository URL and specifying the branch.

- Reference the template by using the file naming convention of ‘Jenkinsfile.yaml‘ using the template keyword to call a template.

// Sample Template for scripting

template:

name: preflight

steps:

- shell: |

if [ ! -f buildArgs.json ]; then

echo "Pre-flight check failed: buildArgs.json not found in workspace root."

exit 1

else

echo "Pre-flight check passed: buildArgs.json found."

fi// Sample with calling multiple templates

template:

name: quality_security_scans

parallel:

- template: code_quality_scan

- template: security_scan// Sample Jenkinsfile.yaml

pipeline:

agent:

label: any

stages:

- stage: Build

steps:

- shell: echo "Building project"

- stage: Test

steps:

- shell: echo "Running tests"

These different approaches provide different trade-offs, which I wanted to summarize to understand some of the trade-offs. My suggestion here is to focus on the the over-arching direction that works for your organization and try it out.

| Dimension | Shared Libraries | Jenkins Templating Engine |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Centralize reusable steps and logic (Groovy functions, pipeline entrypoints) | Enforce template-driven, org-wide pipeline standards |

| Flexibility | High — teams can extend or override functions in their Jenkinsfiles | Lower — templates define the structure, less room for customization per repo |

| Governance | Light to medium — encourages reuse but still leaves freedom to teams | Strong — forces adherence to organizational best practices |

| Setup Complexity | Moderate: requires defining functions and loading library in each Jenkinsfile | Higher upfront: install plugin, create template repo, manage the Jenkinsfile.yaml conventions |

| Best For | Teams that want to reduce duplication but still need repo-level control | Enterprises or large orgs needing consistent pipelines across diverse teams |

| Scaling Impact | Works well for 5–20 teams; risk of divergence if standards not enforced | Scales to 50+ teams with strong compliance needs, at the cost of flexibility |

| Example Jenkinsfile | Small Jenkinsfile required which will should be uniform to call parent shared library | No Jenkinsfile needed in repo; pipeline defined via template in central repo |

Setting up Jenkins is the cheapest option for trying out some of these concepts. Learning to navigate patterns and building out custom solutions for your organization requires trial and error. Start simple, grow with governance. Jenkins lets you move from team-level experiments to org-wide standards without rebuilding from scratch.

What’s Next?

CI/CD pipelines form the foundation for reliable software delivery. A well-designed pipeline aligns with your organization’s functional and non-functional requirements, creating a repeatable process you can trust. In this article, we walked through Jenkins as a sample platform, but the principles apply across many tools. The real takeaway is this: success starts with designing workflows that fit your context, and building in best practices from the beginning.

In the next article, I’ll dive into Infrastructure as Code (IaC) and automation for environment management. With a solid pipeline in place, the natural progression is to define, provision, and evolve environments through code; extending the same reliability and governance you’ve built into your delivery process.